This War Biography has been compiled from at least two biographies written by my father so, whilst the words are his, the order may not be. Where i have made changes, these are indicated with brackets [......italics]. This method may also indicate what I believe may be incomplete, or confused sections.

This story, of my father's WW1 service, is intended, mainly, for his descendents and those close relatives who knew him and are interested but anyone is welcome to read it - this is, I know, stating the obvious as if it were not so, I wouldn't have put it on the Internet but I just wanted to say that!

I would very much welcome, from anyone, any additional information, suggestions, or corrections they may have as I want this story to be as accurate as I can make it but my knowledge of all things military, while getting better, is not good so I would appreciate help!

In September 1940, during a German bombing raid on London, the War Office repository in Arnside Street, London, was hit with the result that more than half the service records, of the nine million men and women, who served in the British armed forces during WW1, were lost. Those records that weren't blown up or set on fire were so saturated by water from the hoses of the firemen that they were unreadable - unfortunately for me, my father's records were among those lost; only his medal card managed to survive but that, at least, did tell me something about him and his service.

With the knowledge that there was no chance of finding any documents relating specifically to my father and his service in the Army, and with no knowledge of military matters, I decided to research the Battalion, of which he was part, with the idea that what they did, he must have done and where they went, he must have gone. This, I realised, could only be considered to be true in the early part of his service; in the very early years, in fact, when he was a young private, but, later on, once the Battalion began to see action this was no longer possible. From the moment he became a runner, his duties, and his location, would have been different from those of the infantryman - this would have been especially so when, later, he transferred to the 'Signals' - but that comes later in his story.

I, recently, visited the Canadian National Vimy Memorial, in Northern France, built and maintained by Canadians to commemorate the battle that began there on 9th April 1917. The battle had nothing to do with my father but the guide started with a description of the army 'runners' - their duties, the dangers, and the terrible trench conditions that all those involved in trench warfare had to endure.

There are many websites on the Internet that give more detailed descriptions of WW1 trench conditions that my father, along with so many others, would have had to live in but I have given some idea HERE. [Steven Newport: I currently have no idea where this link was meant to point but, as and when I get details (or, if) I will endeabvour to update this link. I can, however, strongly recomend the YouTube Channel 'The Great War'.

Steven Newport I have added this section (My Fathers' War History) from a separate biography my father had written, and inserted it in what I feel is the most appropriate place. There may be an element of duplication but it was important to retain the words as written.

Why my father, at the age of sixteen years and eight months, decided to join the army at the start of the first world war, is unknown, and as far as I am concerned, unbelievable. I realise that he couldn't have known what was to come and what a horrific war it would turn out to be but he was never a war-like man and the army just doesn't fit with his personality. He was always a gentleman; an understanding person who saw the other man's point of view and his problems, without the other having to say anything but, in spite of this, he enlisted and I'll never know why.

There is one possible reason I can think of and that's that he joined because most other young men (though older than he was), who worked where he did, at Babcock and Wilcox, in London, may have enlisted as a group, encouraging each other, as many did at the time. After all, it was going to be fun and would be all over by Christmas - wouldn't it?.

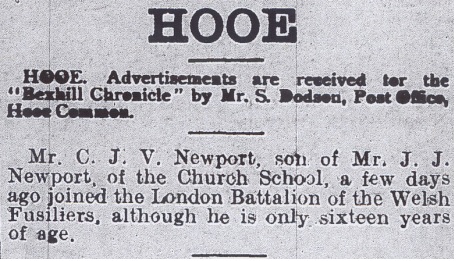

The first mention I came across, of my father enlisting, was an article in the 'Bexhill Chronicle', dated 14th November 1914, where it said, under the heading, 'HOOE':-

'Mr. C.J.V. Newport, son of Mr. J. J. Newport, of the Church School, a few days ago joined the London Battalion of the Welsh Fusiliers, although he is only sixteen years of age.'

From that article, very importantly, we know the regiment he joined, which was the 'Royal Welsh Fusiliers'.

As a non-military man, however, I found the designations of the various parts of the structure of the British Army very confusing - and in spite of a great deal of research and discussion with very knowledgeable WW1 historians, I still do. The above article is a good example - it says, 'the London Battalion of the Welsh Fusiliers', while other documentation refer to it as, simply, the 'London Welsh', and, still others, as the 'Royal Welsh Fusiliers', and the '1st London Welsh Battalion, Royal Welsh Fusiliers'!Working my way through this minefield of confusing information, I found yet another description, which this time, linked his joining the army to his service throughout the war.

15th (Service) Battalion (1st London Welsh) was formed, at London, on 20th October 1914. Later that year, in December, it was attached to the 128th Brigade, 43rd Division. In 1915, on 28th April, it became the 113th Brigade, 38th (Welsh) Division. It then moved to Winchester, in August 1915, landing in France, to join the hostilities, in December 1915.

It turned out to be much more difficult to trace my father's service for his country than I had imagined because the 1914-18 service records of an ordinary British Soldier, someone from the 'other ranks' as opposed to Commissioned Officers, had been kept, securely in a building that, during the Blitz of 1940, was hit by enemy bombs and set on fire.

Many records were destroyed outright but many more were badly damaged by the fire or by the water used trying to put the fire out.

I had to rely on the few pieces of documentation that, for many years, before and after my father died, in 1980, my mother had kept in a drawer. The first, oddly enough, is an incomplete, unfilled 'Attestation Form', which was a form that had to be completed at the time anyone enlisted in the forces. It gives information, on the enlister, such as name, age, address, height, hair and eye colour, previous jobs, and whether or not he has been in prison, as well as many other details. When completed, and signed, the enlister was given his unique Regimental number. In my case, however, where the form had, at some time in the past, been torn into eight pieces and of which only six, dog-eared bits remained in my mother's old hand bag, it only gave the following 'details':

On the front, the date, 'Nov 10 1914', while on the back, the words, written in pencil, 'attested 10-11-1914' and scrawled underneath something that looks like 'BOC' (Battalion Operations Centre?).

Then, there's a signature, 'J.W.King' but no clue as to who he was or why he was signing the form.

Lastly, stamped on the back, in red to purple coloured, upper-case letters the words 'RECRUITING OFFICE - HOLBORN HALL, GRAY'S INN RD'.

Why this almost blank form was kept, by my mother or my father, is unknown but at least it, more-or-less confirms that my father was working, and living, in London at the time, which fits in with what he said, to me, about 'having to leave the nest because there were too many at home'.

Well, I don't think there's any doubt that he was working at Babcock and Wilcox, because of a letter of recommendation written, for him, by them, over a decade after the war.

About the only other records that seem to have survived are his 'Medal List', which gives us a few clues as to his disembarkation in France, and his 'Demobilization Certificate', which gives the following information: -

On June 4th, 1919, Corporal Cuthbert Newport, Regimental number 358870, was transferred to the Army Reserve, from the 3rd. Division Signals. He had enlisted in the Royal Welsh Fusiliers, on 14th November 1914, and, as a Private, service number 21828, had served in the London Welsh Fusiliers and the Royal Engineers.

Because of this paucity of records, I don't really 'know', not for certain anyway, what my father did in the war or where he served. I only have a few stories that he told me and that I remember and a small amount of documentation; some of it useful, like his 'Demobilization Card' that gives a bit of information, some not so useful, such as an 'Attestation Form', which was never filled in - why my mother kept it, for over eighty years, I have no idea - while it's a nice blue colour, faded a bit, it has been torn into six pieces and is dog-eared! Using what I had, however, plus a mystery photograph, which I will explain later, I was able, with a great deal of research, to piece together what he, most probably, saw, went through, and did but, what I would call, hard proof, there isn't much of. I say this because, while I may know what the regiments/divisions/battalions, in which he served, were stationed and/or doing, I have no proof that he was there at the same time - the probability is that he was, but probability isn't proof.

The 'mysterious' photograph, I've put there as well, just to whet your appetite - when I, first, studied it, it looked as though it would tell me nothing but, with help from the on-line 'Great War Forum' much was revealed!

On the 6th November 1915, the Bexhill Chronicle, published an article on Hooe volunteers, and it mentioned my father and showed a photograph of him but, because of the limited technology in the printing of pictures, then, and the fact that I had to scan, into the computer, a photocopy taken of film of an old newspaper (!) it wasn't very clear.

The film, also, had very light and very dark areas, on the same page, so, I had to take two photocopies - one dark enough so I could (just about!) read the words, and the other light enough for me to make out (again, just about!) my father's features. I, then, combined the two to produce a reasonable imitation of the original newspaper article.

'Underneath the picture, it says, SIGNALLER C. J. V. NEWPORT, 1st London Welsh Battalion, Royal Welsh Fusiliers, (son of Mr. and Mrs. J. J. Newport, Hooe)'

[Steven Newport Firstly I seem to been having trouble scaling the image correctly but will sort that later. More importantly the above photograph amazes me as I can see my grandfather in that face - a most odd feeling]

When starting to write my father's story of his part in the First World War, I didn't have much to work on, just the two newspaper cuttings, previously mentioned, the blank, torn-up Attestation form which actually had some information in that it was rubber-stamped with the words, 'Recruiting Office, Holborn Hall, Gray's Inn Rd.', his Medal card, and his Demobilization card', oh, and two of his three medals - the third one is missing and no one in the family seems to know where it went.

I remembered that he'd said he'd been in the 'Signals', and he got there when, as a private in the army, an officer asked all the men if there was anyone who could draw. My father, because he'd been in the Babcock and Wilcox Drawing office before the war, put his hand up - and that's how he joined the 'Signals' - or so he said!

One of his first jobs, in his new position, was to colour in specific areas on ordnance maps because it wasn't possible, at that time, to print maps in colour.

He told me that he was picked to be a 'runner' because he was the fastest at running they had, which made the job sound rather dangerous to me - especially when he talked about running along one side of a hedge listening to the sound of bullets zipping their way through, just above his head!

He also showed me, on many occasions, how to send messages using Morse code, so he'd, obviously, been used to using it, which, of course, having been in the signals, he had would have..I will always remember him repeating the sounds, 'dit' for a quick tap and 'da' for a slower one, so that the mayday call, 'S.O.S.' became, simply, 'dit-dit-dit, da-da-da, dit-dit-dit'. If I'm ever in an emergency and I need help, I can always tap that out - unfortunately, in this day of mobile phones and such, no one will have a clue of what the Morse code is or was and will probably just tell me to 'knock that noise off'!

He mentioned one event, when he was an officer's batman (no, not the idiot, with the bat outfit, leaping tall buildings in a single bound? - oh, no that was Superman, the one with his underpants outside his trousers).

A 'batman' is a soldier assigned to act as a servant for a higher-up commissioned officer; a bit like a 'fag', in a public school; that is if you're English - and nothing like a 'fag', if you're American - trust me.

It appears, so my father said, that he was busy tidying up the officer's quarters, when he came upon a bottle of rum and decided that a little bit wouldn't do him any harm, and the officer wouldn't notice, anyway, so, in the parlance of those who imbibe (that's me folks!), he took a swig. Feeling happier, he took another - and yet another and so on until the bottle was empty but my father wasn't, at which inopportune moment the officer had the temerity to return - never trust an officer! Well, all that my father said, laughing, was that he was found drunk but what punishment he suffered, if any and I suppose he must have, I don't remember him ever saying. If you'd known my father, who only ever had a drink at Christmas, when it was one, small glass of Port ('Whiteways Port', I remember - I don't think you can buy it now), you, too, would find this story incredible!

Then, my mother gave me his 'Demobilization Card', the blank, torn up 'Attestation Form', I mentioned earlier, and an old, worn and cracked photograph that shows him among a large group of soldiers, with no indication as to when, where or why it was taken; and she couldn't tell me, as she didn't know.

After a great deal of research, the asking of many questions, and hours of poring over the photograph with a magnifying glass (yes, I even did that!), a great deal of what was shown in that photograph began to become clear, and so did the story of my father's part in the war. What I have written may not be proven fact but is, I belive, very close to the truth.

The story, from the research I carried out, and my reasons for my conclusions, are, all, given on a separate page, again, because there is much to read.

For some reason, and at some time, neither of which I have been able to discover, my father went from Hooe, in Sussex, up to London. He's still in Hooe, in the 1911 census, aged thirteen, but by the time he reaches sixteen, he's working in the Babcock and Wilcox drawing office, on Farringdon Street, in London.

It's fairly certain that, at that age, he would have stayed with relatives, and I think the most likely ones would have been the Natt family, his uncles and aunts, living at 64 Belsize Road, South Hampstead, about 2 miles from the offices of Babcock and Wilcox. This distance, to a young healthy lad, like my father, born in Hooe where the usual way to get to the town of Bexhill, about 6 miles away, was to walk, would have been no problem and if time was a restraint, there was always the London Underground and the old horse-drawn and the new motor buses.

When I was a young boy, my father often talked about the Natt family, but the name didn't mean anything to me - in fact, I imagined it spelled 'gnat' didn't mean anything to me as I'd never heard of them. In particular, he spoke of his cousin, Victor Natt, who, from what he said, he, so obviously, admired. I feel that he must have got to know the family quite well, much more than he would have done from an occasional visit and, if he'd lived with them in these early years in London, that would explain it.

While he was working for Babcock and Wilcox, Britain declared war on Germany, on 4th August 1918 and the everywhere, people must have been talking about it all around him; in the house, in the streets, and in the drawing office - all young men, enthusiastically egging each other to join up and have some of the glory before it was all over by Christmas. My father must have been caught up in this and, as a result, with mixed feelings of being grown up, and wanting to be like the others, decided to enlist in the Army.

So, on the 10th of November, 1914, he wandered up to the nearest recruitment office, at Holborn Hall, in Gray's Inn Road, just half-a-mile away, and signed on for the Royal Welsh Fusiliers, at the age of sixteen years and eight months.

Just two months before my father signed up, on 13th September, 1914, the War Office sanctioned the raising of a Welsh Brigade, and this came into being, under the command of a Lieutenant-Colonel Owen Thomas, on 30th October. This brigade was given the number 128th and '1st London Welsh' Battalion was to form part of this.

The Battalion came about from a meeting of Welshmen, in London, on September 16th, 1914, presided over by Sir Evan Vincent Evans and, within a very short space of time, recruits came to join up, in large numbers. It wasn't until a month later, on October 29th, 1914, however, that the Battalion became officially recognised and, during those intervening weeks, many of the recruits, too eager to see action, joined other regiments. Sir E. V. Evans, as the Chairman of the Executive Committee of the London Welsh Battalion, kept those that remained, together

With no official headquarters, the Executive Committee set up in, and ran the Battalion from, the 'Inns of Court' Hotel, in Holborn, London.

There are four Inns of Court, in London, and these are all professional legal associations to which each barrister, and judge, in England and Wales must belong in order to practice. Each 'Inn' is controlled by the 'Masters of the Bench', known as 'Benchers', and the 'Benchers of Gray's Inn', lent their Gardens and Squares to the newly formed 1st London Welsh for them to use as drill grounds.

The link between my father, the London Welsh, and Gray's Inn, is a torn, blank 'Attestation Form', kept by my mother in an old handbag, on which is stamped the words, 'RECRUITING OFFICE - HOLBORN HALL - GRAY'S INN RD'.

He must have been given or, perhaps, took two blank Attestation Forms (simply, forms to be completed when enlisting), one of which he filled in and passed on, and the other, still blank apart from the stamp, being the one in my mother's handbag.

My father's next move was when the 1st London Welsh, joined the 43rd Division, at Llandudno, in North Wales, on the 5th of December 1914.

As part-proof of his being billeted at Llandudno, and, therefore, that I have the story correct, there is a hand-written note on the bottom and the back of a typed letter sent to my father, from the 15th (1st London Welsh) Bn., Royal Welsh Association, as a follow-up after a reunion dinner. The interesting part of the note, at this point are the words, 'Do you remember that character at Mrs Edwards, Llandudno, named Mack?' It's not definite proof but it does make it seem more likely. It would have been different if it mentioned, say, Blackpool, instead - but it doesn't - it's Llandudno!

A few months later, on the 29th April, 1915, the 43rd Division was renamed the 38th (Welsh) Division and, because no documentation exists to tell me where my father was and what he was doing, I have to follow the history of that Division - where they went, he must have gone - for a while and within reason, which will become clear later.

In early 1915, the new 38th Division, having no allocated headquarters, was spread across Wales (my father's battalion still being based at Llandudno) from Rhyl to Abergavenny, which meant that they couldn't exercise or train together, not as a whole Division.

While still in Wales, the Infantry, my father included, was given training in open warfare because it was thought that this experience would serve the soldiers better as they would learn trench warfare over in France.

By August, 1915, the 38th had moved to, and was stationed at, Winchester, in Sussex, where, on 29th November 1915, the Division was reviewed by Her Majesty, the Queen, accompanied by H. R. H. Princess Mary; the King, who was to have carried out the review, was unwell.

The next part of the story comes from the War Diaries of the 15th Battalion, the Royal Welsh Fusiliers. The times taken for journeys may seem excessive but it wasn't just the Battalion that was travelling - it was the whole 38th Division (less the artillery that wouldn't arrive until the end of December), roughly 40,000 men in all, plus the equipment necessary in the way of weapons, medical equipment, and supplies.

At a quarter to 6 o'clock, in the morning of Wednesday, 1st December, the Battalion left Winchester, and marched to Southampton, arriving there at 12.30 p.m., a rough distance of 13 miles.

From Southampton, on the 2nd December, at 6.0 pm, they sailed, on the 'T.S.S Queen Alexandra' (T.S.S. = Turbo Steam Ship) to Le Havre, on the north coast of France.

The ship arrived at Le Havre, on 3rd December, where, at 7.00 in the morning, the Battalion disembarked and, as the War Diaries say 'proceeded to Rest Camp' - for 'proceeded' read 'marched' and in full kit carrying all they needed!

There wasn't much of a rest for them, anyway, because, at 6 o'clock in the evening of that same day, they marched to Le Havre railway station where they entrained four hours later, at 10 o'clock, to take them north-eastwards to the town of Blendecques (in the neighbourhood of Roquetoire - roughly 5 Km to the south-south-east of St. Omer, and 50 km south-south-east of Calais).

The Battalion arrived at Blendecques at 6.0 pm the following day and marched to the village of Warne (near St. Omer) where billets were found and the Battalion set up their headquarters.

It's difficult to imagine what the conditions and the journey was like for that number of soldiers - on top of that, they had a war to fight!

From 5th December to the 19th, the Battalion spent the time, at Warne, under training.

Infantry Battalions were made up of 4 companies (very often shortened to 'Coy' or 'Coys'), which were, then, differentiated by the letters 'A','B', 'C', and 'D'. Unfortunately, I've never been unable to discover which Company my father was in - his service record would have told me but this never survived the war.

From the 19th December, these four companies went into more intensive, trench warfare training, by being attached to the 'Guards' - the 1st Scots, the 3rd Grenadier, the 1st Coldstream, and the 2nd Irish.

On 26th December, at 9.00 pm., all the four Companies had finished this course of instruction, which had been, mainly, in trench warfare as this was something that hadn't been possible in England or Wales.

This wasn't the end of their training as, the following day, the Battalion was transported to billets at Merville, where they continued training until 6th January 1916.

Up until this date, it is, reasonably, safe to assume that my father's movements tied in with that of his comrades in the Battalion but, at some time after this, he was made a 'Runner' and, with the change in his duties and, this would no longer have been true.

My father always said that he was made a 'Runner' because he was faster than the others and this I have to accept but I have no idea when he was given this position.

He used to tell me how you would run bent over to keep his head down while he could hear the 'zip' of the bullets flying through the hedge, above his head.

On the 11th June 1916, the Bexhill Chronicle, published an article on Hooe volunteers, and it mentioned my father and showed a photograph of him with, underneath the picture, it says, 'SIGNALLER C. J. V. NEWPORT - 1st London Welsh Battalion, Royal Welsh Fusiliers - (son of Mr. and Mrs. J. J. Newport, Hooe)' - from that article, because it doesn't mention the 'Signals' or the 'Royal Engineers', I have assumed that he had become a 'Battalion runner/signaller' and was not yet part of a 'Divisional Signal Company' - that would come later.

Any battles that the 1st London Welsh were involved in, up to June 1916, therefore, my father might well have, also, played a part - no guarantees but he might, however, from this date onward his duties as a runner or signaller, while being related to the action of the rest of his comrades, would have been different.

I have included, as part of the appendix, pages transcribed from the 15th battalion R.W.F. War Diaries, up to June 1916. It was a lot of hard work, as the writing is not always easy to decipher but I felt that it's the closest I could get to what my father did!

I remember, vaguely, one small story he told me on how he joined either the Signals or the RE (unfortunately, I don't remember which). Apparently, however, when all the men were asked if anyone there could draw. he put his hand up, because, though he was just sixteen going-on seventeen, he had been working in the drawing office of Babcock and Wilcox, in London, in 1914.

As a result, he found himself, so he said with a smile, colouring-in maps. From this small description it sounds as though he had been transferred to the Royal Engineers and, in particular, to the map-making section of one of the Field Survey Units, though I have no idea when this was.

He may well have smiled, then, but he was a signaller and part of his job was to repair any broken communication lines between trenches - unfortunately, the Germans deliberately aimed their big guns

A week after arriving in France about one-third of the division was attached for a week at a time to the Guards and 19th Division then in the line by Fangissart and Neuve Chappelle respectively.

The enemy at that time were fairly quiet, a quietude in force on both sides by the unusual and extremely wet state of the soil. This enabled the division to have a favourable opportunity of learning its duties in trench warfare.

Formed at London on 20 October 1914. December 1914 : came under orders of 128th Brigade, 43rd Division.

27 February 1918 : disbanded in France.

In January, 1916, the Division took over the Neuve Chappelle sector of the line from the 19th Division, and from this period till the beginning of June it was continually in the line holding in turn every portion of the 11th Corps' line from Givenchy on the south to Picantin on the north.

During this period there is but little to record except steady progress in obtaining an ascendancy over the enemy and the carrying out of several raids, the most successful of which was that carried out by the 15th Royal Welch Fusiliers (London Welsh). This was mentioned in general headquarters dispatches as being the third best raid carried out so far in the British Army. The raiding party while out in No Man's land came across an enemy wiring party just finishing their work. Captain Goronwy Owen, commanding the raid, altered his plans on the spot, and with his raiding party quietly followed the working party into their lines and then set upon them.

The enemy was taken by surprise and the greater portion of them was killed while striving to get grenades out of a grenade store.

During this period, Givenchy, with its many mines, constant trench mortaring, and numerous springs that involved frequent repairs to trenches, was the hardest part of the line to hold.

On June the 10th, whilst holding the line near Neuve Chappelle, the Division received orders to proceed south to take part in the Somme fighting of 1916. On the 11th, the whole Division had handed over to the 61st Division and commenced its move south.

Steven Newport the above image came from my fathers files and is entitled Dangerfield. I dont know the source but a quick Google search does show soldiers by the name of Dangerfield. Could there be a source there, or is it merely a reference to the landscape being dangerous. No idea, but if you know please let me know. Steve.Newport93@Googlemail.com

It halted for a fortnight just east of St. Pol, where it trained on a manoeuvre area lent by the French authorities. A trench to trench attack in all its varieties was practised. The Division then moved further south and, at Rubempre, [John's note - A small village, 16 km north-north-east of Amiens.] joined the 2nd Corps, then commanded by Sir Claude Jacob, K. C. B., D.S.O.

At this time, the verbal orders received were that the Division, as part of the 2nd. Corps, was to be prepared to follow the cavalry in the event of a break through and take Bapaume from them.

The check received by the centre and left of the British attack on the 1st July altered these plans and, after marching first north towards ACHEUX and then south to Treux, the Division eventually joined the 15th Corps under Sir Henry Horne, K. C. B., and, on the 5th July, relieved the 7th division in the village of Mametz, and was ordered to prepare for the capture of Mametz Wood.

The task that lay before the Division was one of some magnitude. So difficult had it been thought that in the orders for the attack on the lst July, General Headquarters had left out Mametz wood in their orders, though British troops were to have moved forward to the east and west of it. Moreover, it was capable of being. reinforced easily, the .German second line system being only 300 yards from its northern edge. The 6th to the 9th July were spent in reconnaissance and in testing the enemy's strength by small attacks.

On the 7th July, the 115th Brigade made a small attack on the eastern edge of the wood. Two separate attacks were made that day at 8 a.m. and 11 a.m. by the 16th (Cardiff City) Welsh and the 10th South Wales Borderers (1st Gwents), but neither were successful owing to machine-gun fire not only from the wood but also from some small copses to the north named Hatiron and Sabot respectively. The fire from these enfiladed [JWN's Note - Enfilade and defilade are concepts in military tactics used to describe a military formation's exposure to enemy fire] the attack which in both cases just failed to reach the wood.

On the 9th July it was decided that the time was ripe to attack the wood with the full weight of the Division, and this was carried out at 4.15 a.m. on the 10th July. The task of capturing the eastern portion of the wood was allotted to the 114th Brigade and the western portion to the 113th Brigade, the 115th Brigade being kept in reserve near Minden post and Mametz.

Clearly identifiable - at least in daylight - by the red arm-bands fixed around their left forearm, trench runners (or messengers) were drawn from both a specialised and everyday background. The function of a runner was not simply to bear messages from one area or command unit to another, although this featured prominently.

More critically - and requiring specialisation - qualified runners would be expected to closely familiarise themselves with areas of the front line into which a battalion would soon enter, generally so as to relieve the line's present occupants.

In order therefore to be able to guide the newly-arriving troops with accuracy - particularly given that many such troop movements were undertaken nocturnally under cover of darkness - runners would need to excel both at map-reading and at reconnaissance, generally working in pairs and often with perhaps eight working upon the same task at various parts of the line.

Speed and accuracy were essential in ensuring that the relieving force were in place before daylight; in short, before the enemy force could catch troops in the open with artillery

The 'Signals' were part of the Royal Engineers and these men went where they were needed - [w]hich, usually, meant close to the frontline troops where they provided a means of communication back to the Company and Battalion Headquarters. Initially, Battalions would make use of 'runners' who would, simply, carry the messages, by fleet of foot, from one point to another, running the risk of a bullet from some sharp-eyed enemy soldier.

Later in the war, wired telephones were used but this, if anything, made the job, for the 'Signals' more hazardous as it involved laying landlines or repairing them perhaps, under the watchful eye of a sniper or running the risk of enemy shelling.

So, signal men didn't, necessarily, stay with the rest of the infantry when they went into battle but went with whom and where they were instructed, which, even following the movements of a Company makes it impossible, to say where my father was during the war. The best I can do, is suggest where he might have been and where, in some cases, he probably was.